Charles Rothschild. Picture: The Wildlife Trusts

Dancersend: The History of the Mother of all Nature Reserves

The story of how one wild haven inspired a wealthy banker to found the UK's first nature reserve and start the conservation movement.

The history of Dancersend - a presentation by Mick Jones (https://youtu.be/hmnep3V9Kno)

Celebrating the 80th anniversary of this fascinating nature reserve, volunteer warden Mick Jones outlines its history and special place in the development of conservation in the UK.

19th century: the seeds of a movement are sown

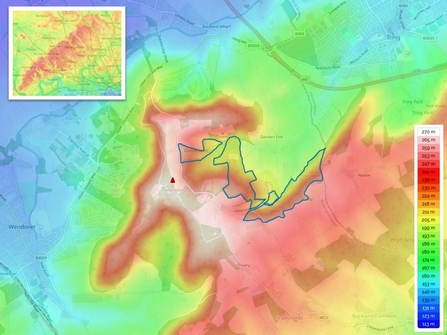

A relief map of the area around Dancersend in Buckinghamshire, with the boundaries of BBOWT's Dancersend Nature Reserve in blue. The map shows the almost unique topography of the area which gives rise to some rare sheltered south-facing chalk grassland slopes. Picture: en-hk.topographic-map.com / Mick Jones

For centuries before the 1800s, the hills around Dancersend in Buckinghamshire were a complex of woodlands and grassy clearings with changing ownership and management.

The name derived from the Dancer family who had lived in the Buckinghamshire area since the 13th century and built Dancers End House which still stands near the nature reserve. An ‘end’ was a local Medieval name for a valley, after the roads which ran through valleys and ended at freshwater springs.

A postcard of the Rothschild family home - Tring Park. Reproduced with the permission of The Trustees of The Rothschild Archive.

In 1872, Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild - head of the famous international banking family - bought the nearby Tring Park Estate and also acquired land around Dancersend.

In the 1880s, Lord Rothschild's sons Walter and Charles started going out and collecting butterflies in the lush wildflower meadows of the Dancersend Crong Valley: these adventures would inspire a love of wildlife in the young Charles that went on to change his life and the world.

1890s and 1900s: The UK's first nature reserve

Charles Rothschild. Picture: National Portrait Gallery

After attending Harrow School in London, Charles went to work at the family bank NM Rothschild and Sons in London, but devoted his free time to studying natural history. With a passion for insects, he collected some 260,000 individual fleas and described about 500 new flea species including the bubonic plague vector flea, Xenopsylla cheopis.

In 1899, he purchased two acres of Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire for £10 and gifted it to the National Trust, which was already managing the land. The site is often regarded today as the UK's first nature reserve, and this small move marked the start of a lifelong mission to protect land for wildlife for which Charles Rothschild is considered a pioneer of conservation in Britain.

As well as purchasing other plots of land around the country to protect for nature, he also managed his own estate at Ashton Wold in Northamptonshire to maximise its suitability for a wide range of wildlife, especially butterflies.

1912: Founding of the SPNR and the Rothschild Reserves

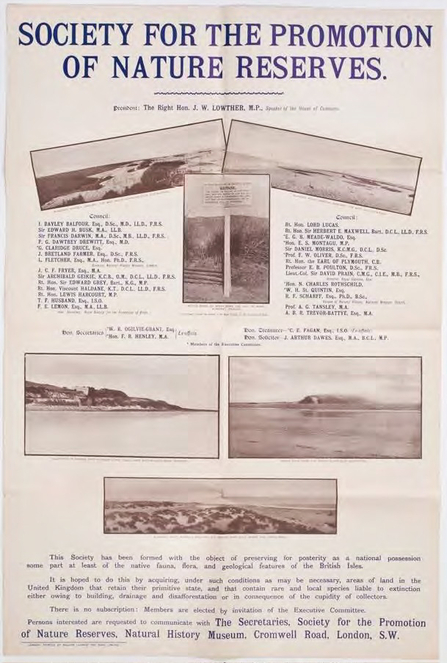

An early poster advertising the formation of the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR). Picture: The Wildlife Trusts

In May 1912, a month after the Titanic sank, Charles Rothschild held a meeting at the Natural History Museum in London to discuss his idea for a new organisation to save the best places for wildlife in the British Isles. This meeting led to the formation of the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR).

Rothschild's vision was to identify and secure protection for the British Isles' most important wildlife sites. His vision was a radical one that led to nature conservation as we know it. The initial aim of Rothschild's society was to create a list of Britain's finest wildlife sites so they could be protected for the future. Three years of information gathering followed - the first ever national survey of wildlife sites - in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

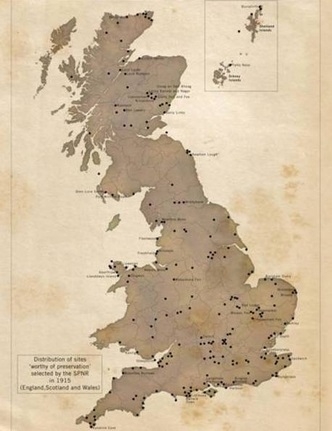

A map showing the 284 'Rothschild Reserves' across the United Kingdom in 1915. Picture: The Wildlife Trusts

Rothschild and his friends (including Neville Chamberlain who went on to become Prime Minister) were looking for the 'breeding-places of scarce creatures', the 'localities of scarce plants' and areas of 'geological interest'. By 1915 they had compiled a list of 284 sites 'worthy of preservation' – known as the Rothschild Reserves.

While some have been devastated by development, or simply vanished in the mists of time, those that survive are now all SSSIs and/or designated nature reserves, many of them protected by law. The original list included now classic nature reserves and well-known wildlife hotspots, at least eight of which are now BBOWT reserves. The SPNR acquired its first nature reserve in 1919 when Charles Rothschild gifted it Woodwalton Fen in Cambridgeshire.

Naturalists at Woodwalton Fen, Huntingdonshire, in 1935. Woodwalton Fen was bought by Charles Rothschild in 1910 and gifted to the SPNR in 1919. Picture: The Wildlife Trusts

The 1920s: Charles Rothschild’s death and legacy

Charles Rothschild. Picture: The Wildlife Trusts

In 1922, Charles Rothschild acquired Dancer's End woods and grassy clearings to become a nature reserve after the liquidation sale of his family’s Halton Park estate. The following year, at the age of 46, Charles Rothschild committed suicide. He had been suffering from encephalitis - an inflammation of the brain with unpleasant effects - but his death was a profound shock to his wife and four children. Because of his untimely end, he never got to see how the conservation movement which he helped to start snowballed in popularity: in 1949, the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act created the first Government conservation agency (the Nature Conservancy Council) and the first National Parks and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). In 1959 the SPNR which Charles founded took on the role of a national association to represent local conservation groups around the country. In the same year, a group of naturalists held a meeting in Oxford to form the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Naturalists' Trust (BBONT).

1940s-1960s: Miriam Rothschild fights to save Dancersend from war and more

An entrance to Dancersend nature reserves, and an original sign from the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves. Photo by Mick Jones

In 1941, Charles Rothschild's son and daughter, Miriam and Victor, gifted the 78-acre Dancersend site to the SPNR to be an official nature reserve in memory of their father. Miriam became a highly respected entomologist and ecologist, and maintained a keen interest in Dancersend in particular, chairing its management committee for many years.

This was fuelled by the fact that the reserve then went through a period of huge change: in 1943, at the height of the Second World War, the two main woods - Bittams and Round Spring - were completely cut down to provide timber for the war effort, and the adjacent fields were ploughed to grow vital food crops. In 1955 the Forestry Commission was invited to replant the woods with beech and non-native conifers to produce yet more timber.

The Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR) 1968 handbook, including an article by Miriam Rotshchild on her new management plan for Dancersend Nature Reserve, then owned by the SPNR. Picture: Mick Jones

In the 1950s and 1960s, the site's ecology was damaged again when myxomatosis - then spreading across the country - decimated the rabbit population: with no rabbits there to ‘mow the lawn’, grassy clearings 'scrubbed up' and became overgrown. By this stage, much of the habitat that had once made the area magical and inspired the young Charles was gone. In the 1960s, Miriam Rothschild began an SPNR experiment to rescue the precious chalk grassland at Dancersend by establishing 'meadow plots' where hawthorn and other scrub was cut down by hand and new grazing techniques were tried out to maintain grassy, open areas. The experiment helped to inform conservation for decades to come.

1968 – present: BBOWT takes charge

Dancersend nature reserve near Aylesbury. Picture: Pete Hughes

In 1968, Miriam Rothschild and the SPNR invited the newly-formed BBONT to take over the management approach that she had pioneered in the central scrub/ grassland area. The following year, the SPNR handed the central part of Dancersend to BBONT on a 21-year lease. Throughout the 1970s, BBONT continued to clear extensive areas of scrub and secondary woodland to restore the kind of grassland where Charles and his brother had hunted for butterflies nearly a century before. The Trust was eventually given the freehold of the whole reserve in 1997, and in the 1980s and 90s it acquired adjoining parcels of land (leasing the Waterworks and Crong Meadow from Thames Water in 1987 and buying the Extension Fields in 1999) to expand the reserve to 150 acres.

In 1994, BBONT started working with neighbouring landowners to manage the adjacent SSSI land on Coombe Hill and influence the management of other areas in the valley: this helped to bolster the precious habitat already being maintained. The following year, the SPNR founded by Charles Rothschild officially changed its name to The Wildlife Trusts: it now represents 46 local Trusts across the UK which collectively look after over 2,300 nature reserves.

In 2015 BBOWT - as it was now known - expanded its Dancersend reserve again by taking over management of neighbouring Pavis Woods from Buckinghamshire Council. At 211 acres, Dancersend with Pavis Woods is now the largest and oldest of BBOWT's Buckinghamshire reserves.

In 2021, to mark 80 years since Miriam and Victor gifted the site to the SPNR in memory of their father, the Rothschild Foundation gave BBOWT a £90,000 grant for a host of enhancements at the reserve. Among these will be new interpretation boards which, for the first time, will tell visitors some of the site’s history, and how none of it might ever have come to pass were it not for Charles Rothschild’s incredible vision.

Take a virtual tour of Dancersend nature reserve with volunteer warden Mick Jones